Introduction

Greetings, fellow developers!

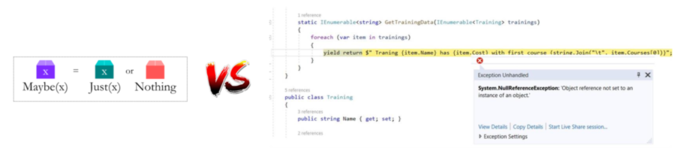

In the realm of software development, null reference exceptions have notoriously been dubbed the “billion-dollar mistake”. This pervasive issue spans across programming languages, leading to runtime errors that not only are challenging to debug but also to resolve. Specifically, in C#, numerous strategies have been proposed to tackle this problem. Among these, a notable solution emerges from the principles of functional programming: the Maybe Monad. The Maybe Monad presents an elegant approach to gracefully handle potential null values, significantly reducing the risk of null reference exceptions.

This blog post aims to explore the utility of the Maybe Monad within C#, offering insights on how it can enhance code reliability and readability. Join us as we delve into the world of functional programming to mitigate the infamous null reference dilemma, marking a pivotal shift towards more resilient software development practices.

TL;DR

I’ve shared the code of this post as a gist. Jump to Gist

Understanding Null Reference Exceptions in C#

A null reference exception is a common yet dreaded error in C#. It occurs when you try to access a member (such as a method or property) of an object that is currently null—that is, it points to no instance in memory. This situation is especially prevalent when working with objects that may not be properly initialized in certain execution paths of your application.

Consider this straightforward yet illuminating example:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

class Program

{

static void Main(string[] args)

{

var trainings = TrainingService.GetTrainings();

foreach (var item in GetTrainingData(trainings))

{

Console.WriteLine(item);

}

}

static IEnumerable<string> GetTrainingData(IEnumerable<Training> trainings)

{

foreach (var item in trainings)

{

yield return $" Traning {item.Name} has {item.Cost} with first course {item.Courses[0]}";

}

}

}

public class Training

{

public string Name { get; set; }

public string Courses { get; set; }

public string Cost { get; set; }

}

public static class TrainingService

{

public static IEnumerable<Training> GetTrainings()

{

var trainings = new List<Training>();

trainings.Add(new Training() { Name = "c# 8.0", Cost = "$20" });

trainings.Add(new Training() { Name = "JS", Cost = "$40", Courses = "Basic, Data type, loops etc" });

return trainings;

}

}

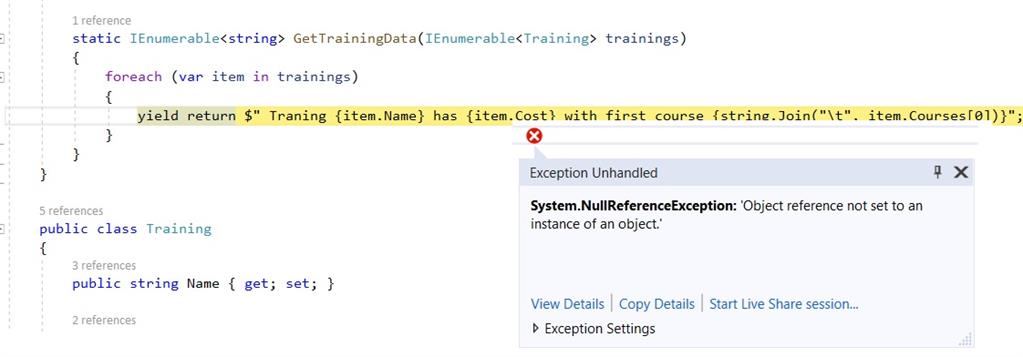

If you notice in GetTrainingData() to get the first element of Course, this could create an exception here if Course is null. But currently compiler does not detect this hidden null item and informs you to take care.

if you execute this code, you will get the null reference.

To prevent such exceptions, developers often resort to inserting numerous null checks (if (object != null)) throughout their code. However, this practice can lead to code that is not only cumbersome to read and maintain but also detracts from the business logic by cluttering it with defensive programming boilerplate.

This section introduces the challenge at hand: how can we more elegantly manage the possibility of null values? As we will see, the Maybe Monad offers a compelling pattern for addressing this challenge, promoting a cleaner, more maintainable approach to null handling in C#.

Enter the Maybe Monad

In the functional programming paradigm, a Monad serves as a powerful design pattern, facilitating the chaining of operations and managing side effects in a controlled manner. Think of it as a blueprint for performing a sequence of steps, where each step is dependent on the outcome of the previous one. This concept, while abstract, is instrumental in handling computations elegantly.

Among various types of monads, the Maybe Monad stands out for its simplicity and utility, particularly in addressing the nullability dilemma. It acts as a container for a value that may or may not exist—thus the name “Maybe.” This is a profound shift from the traditional approach where a variable could hold either a specific value or null, leading to the dreaded null reference exceptions.

The Maybe Monad encapsulates this concept as a generic type, Maybe<T>, which can exist in one of two states:

- Just (or Some): Signifies that a value of type T is present.

- Nothing (or None): Indicates the absence of a value.

This simple construct allows you to encapsulate optional values in a way that forces the consumer of the value to explicitly handle both cases: when the value is present and when it is not. This explicitness significantly reduces the chances of encountering null reference exceptions.

Implementing the Maybe Monad in C#

While C# does not inherently support the Maybe Monad, its flexible type system allows us to implement this pattern with relative ease. Below is a streamlined version that encapsulates the core idea of the Maybe Monad:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

public class Maybe<T>

{

public static readonly Maybe<T> None = new Maybe<T>();

public T Value { get; }

public bool HasValue { get; }

private Maybe()

{

HasValue = false;

}

public Maybe(T value)

{

Value = value ?? throw new ArgumentNullException(nameof(value));

HasValue = true;

}

}

This implementation defines a class Maybe<T> with a private constructor for the None case and a public constructor for the Just case. To ensure robustness, the public constructor throws an ArgumentNullException if a null value is passed, reinforcing the intention that Maybe<T> should explicitly handle nulls, not implicitly contain them.

Utilizing the Maybe Monad

Adopting the Maybe Monad in your C# projects encourages a more explicit handling of optional values, significantly reducing the likelihood of null reference exceptions. By refactoring methods to return Maybe<T> instead of directly returning a type T or null, you effectively communicate to the method consumers that they must handle the possibility of an absent value.

Refactoring Methods for Safety

Consider the following example, which showcases a method that attempts to retrieve a user by their ID:

1

2

3

4

5

public Maybe<User> GetUserById(int id)

{

var user = _userRepository.GetById(id);

return user != null ? new Maybe<User>(user) : Maybe<User>.None;

}

In this implementation, the GetUserById method returns a Maybe<User> instead of a User object directly. This return type explicitly signals to the caller that they might receive a user object or they might not, depending on whether the user exists.

Handling the Maybe Value

When consuming a method that returns a Maybe<T>, you must check if a value is present using the HasValue property before accessing the value:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

var maybeUser = GetUserById(userId);

if (maybeUser.HasValue)

{

Console.WriteLine($"User found: {maybeUser.Value.Name}");

}

else

{

Console.WriteLine("User not found.");

}

Benefits of MayBe Monad

Incorporating the Maybe Monad into your C# projects can significantly elevate the quality of your codebase through several key advantages:

Improved Code Safety

The Maybe Monad inherently encourages a more defensive programming style by making nullability explicit. By requiring consumers to handle both the presence and absence of a value, it drastically reduces the chances of unhandled null reference exceptions—one of the most common runtime errors. This shift towards explicit null handling means that many potential errors are caught at compile time rather than at runtime, enhancing the overall stability of applications.

Enhanced Readability and Maintainability

Code utilizing the Maybe Monad is often clearer and more intentional. The presence of Maybe<T> explicitly signifies that a value might be missing, guiding developers to naturally consider and handle this scenario. This clarity makes code easier to understand for new team members and maintains its readability over time, as the intention behind null checks is always clear.

Ease of Integration and Use

Despite its roots in functional programming, the Maybe Monad can be seamlessly integrated into C# projects, thanks to C#’s support for generic types and implicit conversions. This ease of use encourages developers to adopt Maybe without significantly altering their current programming style or learning a completely new paradigm.

Promotes a Shift Towards More Robust Error Handling

By adopting Maybe, teams are naturally led towards a mindset that prioritizes robust error handling and preventive programming practices. This can have a broader educational effect, increasing awareness of functional programming principles and their benefits, even in an object-oriented context.

However, it’s important to consider that introducing functional programming concepts like Monads into primarily imperative/OOP codebases can have a learning curve for some developers. Adequate team training and code documentation are essential for a smooth transition.

Enhancing the implementation for performance and immutability

The previous implementation responds to the MayBe Monad principle, but we can enhance it for more optimization and code reusability, let’s see how we can achieve that:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

37

38

39

40

41

42

43

44

45

46

47

48

49

50

51

52

53

54

55

56

57

58

59

60

61

62

63

64

65

66

public readonly struct MayBe<T> : IEquatable<MayBe<T>> where T : class

{

private readonly T _value;

public MayBe(T value)

{

_value = value;

HasValue = !(value is null);

}

public static MayBe<T> None => new MayBe<T>(default);

public readonly bool HasValue { get; }

public T Value

{

get

{

if (!HasValue)

{

throw new InvalidOperationException();

}

return _value!;

}

}

public static implicit operator MayBe<T>(T value)

=> value is null ? None : new MayBe<T>(value);

public static bool operator !=(MayBe<T> left, MayBe<T> right)

=> !(left == right);

public static bool operator !=(MayBe<T> left, T right)

=> !(left == right);

public static bool operator !=(T left, MayBe<T> right)

=> !(left == right);

public static bool operator ==(MayBe<T> left, MayBe<T> right)

=> left.Equals(right);

public static bool operator ==(MayBe<T> left, T right)

=> left.Equals(right);

public static bool operator ==(T left, MayBe<T> right)

=> right.Equals(left);

public bool Equals(MayBe<T> other)

=> HasValue == other.HasValue && (!HasValue || _value!.Equals(other._value));

public override bool Equals(object obj)

=> obj is MayBe<T> other && Equals(other);

public override int GetHashCode()

=> HasValue ? _value!.GetHashCode() : 0;

public T GetValueOrDefault()

=> !HasValue ? default : _value;

public T GetValueOrDefault(T defaultValue)

=> HasValue ? _value! : defaultValue;

public override string? ToString()

=> HasValue ? _value?.ToString() : "";

}

This enhanced implementation of the Maybe<T> monad as a readonly struct introduces several optimizations and features that improve its performance, usability, and safety. Let’s break down the key improvements and provide some additional insights on how they contribute to a more robust and efficient design.

Key Improvements and Insights

Struct Implementation

- Memory Efficiency: By defining Maybe<T> as a readonly struct, you leverage the memory efficiency of value types in C#. Structs are allocated on the stack, which can reduce the overhead associated with heap allocation and garbage collection for objects that have a short lifecycle.

- Immutability: Marking the struct as readonly enforces immutability, ensuring that the state of a MayBe<T> instance cannot be modified after its creation. Immutability is a core principle in functional programming, leading to safer and more predictable code, especially in multi-threaded environments.

Generic Constraint

- Reference Type Constraint: The where T : class constraint ensures that Maybe<T> can only be used with reference types. This design choice directly addresses the null reference problem by making Maybe<T> inapplicable to value types, which cannot be null and therefore don’t suffer from the same nullability issues.

Exception Handling for the Value Property

- Enforced Presence Check: Throwing an InvalidOperationException when attempting to access the Value property without a valid value reinforces the monad’s purpose. It requires consumers to explicitly check for the presence of a value with HasValue, aligning with the monadic goal of making error states explicit and avoiding runtime exceptions related to null dereferencing.

Operator Overloads

- Intuitive Usage: Overloading equality operators and providing an implicit conversion from T to Maybe<T> enhances the usability of the monad. These operators allow Maybe<T> instances to be compared directly to their underlying values and to each other, integrating seamlessly with C#’s type system and making the monad more intuitive to use in everyday scenarios and facilitating the refactoring of the existing code to the Monad paradigm.

Additional Enhancements

- GetValueOrDefault Methods: The GetValueOrDefault methods provide a safe way to access the Maybe value, returning a default value if no value is present. This feature further supports the safe handling of optional values, allowing developers to specify fallback values in a fluent and expressive manner.

- ToString Override: Implementing ToString to return the underlying value’s string representation or an empty string if no value is present improves the debuggability and logging capabilities of your code when using Maybe<T> instances.

Extending the Pattern with Functional Techniques

To further leverage the power of the Maybe Monad, we can use functional techniques such as map and filter operations. These can transform or use the value within a Maybe without explicitly checking HasValue, making our code even cleaner and more expressive:

Safer Value Access

We’ll add two methods to MayBe<T>: Match and OrElse. Match allows the caller to specify actions for both when a value is present and when it’s not, while OrElse provides a way to specify a fallback value.

Extension Methods for Functional Composition

We’ll create extension methods Bind, Map, and Filter. These methods will allow chaining operations on MayBe<T> instances, enabling more functional and expressive data handling.

Here’s how these additions might look:

1

2

3

4

5

6

7

8

9

10

11

12

13

14

15

16

17

18

19

20

21

22

23

24

25

26

27

28

29

30

31

32

33

34

35

36

public readonly struct MayBe<T>

{

// Existing implementation here...

// Match method to handle both cases with actions

public TResult Match<TResult>(Func<T, TResult> some, Func<TResult> none)

=> HasValue ? some(_value) : none();

// OrElse method to provide a fallback value

public T OrElse(T fallback)

=> HasValue ? _value : fallback;

public T OrElse(Func<T> fallback)

=> HasValue ? _value : fallback();

}

// Extension methods for MayBe<T>

public static class MayBeExtensions

{

// Bind: Apply a function that returns a MayBe to the value inside the original MayBe

public static MayBe<TResult> Bind<T, TResult>(this MayBe<T> maybe, Func<T, MayBe<TResult>> binder)

where T : class

where TResult : class

=> maybe.HasValue ? binder(maybe.Value) : MayBe<TResult>.None;

// Filter: Apply a predicate to the value inside MayBe, returning None if the predicate is not satisfied

public static MayBe<T> Filter<T>(this MayBe<T> maybe, Func<T, bool> predicate)

where T : class

=> maybe.HasValue && predicate(maybe.Value) ? maybe : MayBe<T>.None;

// Map: Transform the value inside MayBe if it exists

public static MayBe<TResult> Map<T, TResult>(this MayBe<T> maybe, Func<T, TResult> mapper)

where T : class

where TResult : class

=> maybe.HasValue ? new MayBe<TResult>(mapper(maybe.Value)) : MayBe<TResult>.None;

}

Explanation

- Match Method: This method allows callers to handle both the presence and absence of a value through delegate parameters, making the MayBe<T> type more versatile. It’s a direct way to extract the value or compute an alternative result without throwing exceptions.

- OrElse Methods: These methods provide ways to specify fallback values directly or through a function, offering a safety net for when MayBe<T> does not contain a value. The second OrElse overload taking a Func<T> is useful when the fallback value is expensive to compute or retrieve.

- The Map Extension Method: allows for the transformation of the value inside a MayBe<T> if it is present.

- The Bind Extension Method: is used to apply a function that also returns a MayBe<T> to the value, useful for chaining dependent operations that may also result in a MayBe<T>.

- The Filter Extension Method: applies a predicate to the value, turning the MayBe<T> into None if the predicate is not satisfied, which is useful for conditional logic in a fluent API style.

Here is an example of using MayBe Monad in a proper functional way:

1

2

3

4

5

var userName = GetUserById(userId)

.Map(user => user.Name)

.OrElse(() => "Anonymous");

Console.WriteLine($"Welcome, {userName}!");

In this example, Map applies a function to the value inside the Maybe, if present. OrElse provides a fallback value or action if the Maybe is empty. This pattern not only eliminates the need for explicit null checks but also embraces a more declarative style of programming, where the focus is on what you want to achieve rather than how.

MayBe Monad VS Nullable Reference Types in C# 8.0 and Beyond

With the introduction of C# 8.0, developers gained a powerful tool against null reference exceptions: nullable reference types. This feature enhances type safety by making the nullability of reference types explicit, thus pushing potential null issues from runtime errors to compile-time warnings.

Conversely, the Maybe Monad—a concept borrowed from functional programming—wraps values in a container that explicitly requires handling for both their presence and absence. This method not only deals with nullability but also encourages a shift towards more expressive and safe coding practices.

Given these advancements, it’s worth exploring how they differ and which might better suit your development needs.

Nullable Reference Types in C# 8.0 and Beyond

Advantages

- Built into the Language: No external libraries or custom implementations are required. It’s a language feature that’s supported by the compiler.

- Ease of Adoption: You can gradually adopt nullable reference types across your codebase, making it easier to integrate into existing projects without significant refactoring.

- Tooling Support: IDEs and static analysis tools can provide immediate feedback on potential nullability issues, helping to catch problems early in the development cycle.

Considerations

- Not Foolproof: While nullable reference types can significantly reduce null reference exceptions, they don’t eliminate the possibility entirely. Runtime checks and proper validation are still necessary for edge cases.

- Learning Curve: Developers need to understand the implications of enabling nullable reference types and how to work with them effectively.

The Maybe Monad Approach

Advantages

- Explicit Value Semantics: The Maybe Monad makes the existence of a value explicitly part of the type system, which can make the code more readable and intention-revealing.

- Encourages Functional Programming Practices: Using the Maybe Monad can lead developers towards more functional programming patterns, which can improve code modularity and testability.

- Flexible and Powerful: Beyond just handling nulls, Monads can be used to compose operations and manage side effects in a more controlled manner.

Considerations

- Requires Custom Implementation or Library: Unlike nullable reference types, the Maybe Monad is not built into C#. You’d need to implement it yourself or use a library.

- Increased Complexity: For teams unfamiliar with functional programming concepts, the Maybe Monad might introduce a learning curve and potentially make the codebase harder to understand at first.

Which is Better?

The choice between using nullable reference types and the Maybe Monad isn’t strictly about which is better overall, but rather which is more suitable for your project’s needs and your team’s familiarity with functional programming concepts. So The Answer is “It depends!, and “Everything in software design/architecture is a tradeoff”, but:

- If your goal is to integrate null safety with minimal overhead and you’re working within a codebase that already follows traditional C# patterns, nullable reference types offer a straightforward way to enhance type safety with strong tooling support.

- If you’re looking to embrace functional programming principles more fully, or you need the additional control and expressiveness that comes with the Maybe Monad (such as chaining operations and handling optional values in a more declarative manner), then Maybe Monad could be the right choice.

Ultimately, both approaches aim to make your code safer and more robust by reducing the likelihood of null reference exceptions, and your choice should align with your project’s specific requirements and your team’s coding preferences.

Conclusion

In the journey through the intricate landscapes of C# programming, null reference exceptions have long been a notorious challenge, often leading to runtime errors that can be both perplexing and time-consuming to debug. However, the adoption of the Maybe Monad presents a paradigm shift, offering a robust and elegant solution to this pervasive problem. By reimagining error handling through the lens of functional programming, we can transform our approach to nullability, enhancing both the safety and readability of our code.

The Maybe Monad not only mitigates the risk of null reference exceptions but also encourages a more thoughtful and explicit handling of optional values. This shift towards explicitness helps prevent errors before they happen, making our software more reliable and our developer experience more pleasant. Moreover, integrating Maybe Monad into our C# projects nudges us towards adopting functional programming principles, fostering a coding environment where safety and expressiveness go hand in hand.

As we’ve explored the implementation and practical applications of the Maybe Monad, it’s clear that this pattern has the potential to significantly impact how we write and think about C# code. By embracing Maybe, we not only address the specific issue of null references but also open the door to a broader transformation in our programming practices. The functional programming concepts embodied by Maybe Monad can lead to cleaner, more maintainable, and less error-prone codebases.

In conclusion, the journey to mastering the Maybe Monad is not just about avoiding null reference exceptions—it’s about embracing a coding philosophy that values safety, clarity, and intentionality. As we continue to evolve our practices and explore new paradigms, the Maybe Monad stands out as a powerful tool in our arsenal, promising a future where C# programming is both more enjoyable and more effective. So, let’s embark on this journey together, transforming our code and our mindset, one Maybe at a time.

that’s all folks! Keep your code cleaner ![]()

Gist

I’ve shared the code seen in this post as a gist